Reference managers and I have a long history. All the way back in 20041, when I was writing my first paper, my workflow went something like this:

Reference managers and I have a long history. All the way back in 20041, when I was writing my first paper, my workflow went something like this:

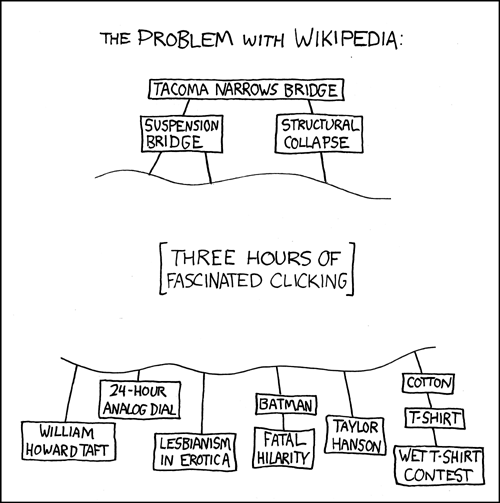

“I need to cite Drs. A, B, and C here. Now, where did I put that paper from Dr. A?” I’d search through various folders of PDFs, organized according to a series of evolving categorization schemes and rifle through ambiguously labeled folders in my desk drawers, pulling out things I knew I’d need handy later. If I found the exact paper I was looking for, I’d then open Reference Manager (v6, I think) and enter the citation details, each in their respective fields. Finding the article, I’d the select it and add it to the group of papers I was accumulating. If it didn’t find it, I’d then go to Pubmed and search for the paper, again entering each citation detail in its field, and then do the required clicking to get the .ris file, download that, then import that into Reference Manager. Then I’d move the reference from the “imported files” library to my library, clicking away the 4 or 5 confirmation dialogs that occurred during this process. On to the next one, which I wouldn’t be able to find a copy of, and would have to search Pubmed for, whereupon I’d find more recent papers from that author, if I was searching by author, or other relevant papers from other authors, if I was searching by subject. Not wanting to cite outdated info, I’d click through from Pubmed to my school’s online catalog, re-enter the search details to find the article in my library’s system, browse through the until I found a link to the paper online, download the PDF and .ris file(if available), or actually get off my ass and go to the library to make a copy of the paper. As I was reading the new paper from the Dr. B, I’d find some interesting new assertion, follow that trail for a bit to see how good the evidence was, get distracted by a new idea relevant to an experiment I wanted to do, and emerge a couple hours later with an experiment partially planned and wanting to re-structure the outline for my introduction to incorporate the new perspective I had achieved. Of course, I’d want to check that I wouldn’t be raising the ire of a likely reviewer of the paper by not citing the person who first came up with the idea, so I’d have some background reading to do on a couple of likely reviewers. The whole process, from the endless clicking away of confirmation prompts to the fairly specific Pubmed searches which nonetheless pulled up thousands of results, many of which I wasn’t yet aware, made for extraordinarily slow going. It was XKCD’s wikipedia problem writ large. Continue reading →

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=7b0685af-2241-4f5c-8519-19c653a47467)