AI-assisted research is an exciting prospect – no more laborious keyword searches, scanning abstracts, and organizing PDFs – but do they live up to the promise? I explored this question using Elicit’s Systematic Review tool. I found a Cochrane Review on a topic and then asked Elicit the same question. I compared the two on retrieval of relevant studies, selection of studies to include, extraction of data, assessment of risk of bias, synthesis of evidence, and assessment of evidence quality. I found the report said, qualitatively and approximately, a similar thing for some primary and secondary outcomes as the Cochrane review. The Elicit report could be used by an expert to reach a similar high-level understanding as they would have gotten from the Cochrane review, but the most important between-study comparisons were not made within the report. The tool was not able to assess included studies for risk of bias, pool data across studies, or assess evidence quality. Differences were also found in study selection and detail reported for key findings.

AI and Bioterrorism: Risks Explained

How AI can be used for bioterrorism

Humanity has climbed to the top of the food chain, but as the pandemic demonstrated, it’s a precarious perch. It’s not just directly pathogenic viruses that we need to worry about, either. Small molecules and proteins synthesized by bacteria also pose a risk to life, to crops and livestock, and to the environment. These risks would be realized by a terrorist through genetic engineering, the means by which new capabilities are introduced to an organism through changes in its DNA. This is a time-consuming and laborious process that can be vastly accelerated with AI and biological design tools. A terrorist might design a novel virus that causes human illness, one which kills livestock, makes soil infertile, or fouls the ocean.

How dangerous are current AI systems?

Continue reading

Where’s the art in artificial intelligence?

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” – John 1:1 KJV

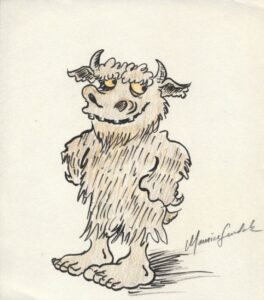

When I think about creative works generated by generative AI, I think about golems. According to legend, Rabbi Yehudah Loew created a automaton from clay to protect the Jews of Prague by animating a soulless lump of clay with the Word of God. Like the Rabbi of folklore, when we write or produce a work of art, we like to think we’re doing something that imbues our work with soul. People say an image created by GenAI lacks the “creative spark”, but what does this really mean? What distinguishes an illustration by Sendak or Doré or Geiger from a similar work created by prompting Midjourney?

Imagine Hugging Face puts on an event where they put a generated illustration next to a work from a famous illustrator and ask an art critic to point out differences. The art critic will get deep in the weeds and point out various differences, then they’ll ask another art critic, who’ll emphasize different distinctions, then another will identify still others as crucial and then Hugging Face will say, “Aha! The critics couldn’t reproducibly find differences and therefore there really are none!” Lots of breathless media headlines and dunking on critics will ensue, unless…

Continue reading

Do we really want a global town square?

In 2005, Lawrence Summers, president of Harvard, former US Secretary of the Treasury and Chief Economist of the World Bank, gave a speech at NBER where he discussed some employment data. He said he was offering a positive, observational view and not a judgemental or normative view.

…the data will, I am confident, reveal that Catholics are substantially underrepresented in investment banking […], that white men are very substantially underrepresented in the National Basketball Association, and that Jews are very substantially underrepresented in farming and in agriculture. These are all phenomena in which one observes underrepresentation and I think it’s important to try to think systematically and clinically about the reasons for underrepresentation.

He thought that these prefatory statements, and that he was attempting to be a little provocative and not speaking on behalf of Harvard, would have opened up a thoughtful discussion of various factors leading to under-representation of women in tenured positions in science at top universities. He could not have misjudged his audience more poorly.1 Continue reading

The big thing LLM interfaces are missing: dialogue

Daniel Tunkelang brought my attention to a lovely rant from Amelia Wattenberger about the lack of affordances in chat interfaces and I began to wonder what it means for a chat interface to have an affordance. In other words, what’s the obvious thing to do with a chat interface like it’s obvious that a glove can be put on a hand to protect it? The obvious thing to do is to have a conversation, but people building products miss the most important thing about conversation: it’s a process, not a transaction. Product people think the obvious thing to do with an LLM chat interface is to ask questions and get answers and their critics quickly respond that the answers are merely plausible sentences and any truth is incidental. This whole thing has become tiresome and no one is putting their finger on the heart of the issue to move the conversation forwards. Taking a step back to consider how a conversation with a subject matter expert goes quickly reveals the confusion here. How does a conversation with a subject matter expert go? You start by asking bad questions and you get questions from them in return and then you ask better ones and through a process of back-and-forth dialogue, you end up with a better understanding that is often very different from what you thought you were after when you started the conversation, as this person seeking help with a regular expression to parse HTML famously discovered. It’s the process of dialogue that’s the important thing here, so thinking of the exchange in terms of a transaction is just a confused conceptual model. To make an LLM product that really delivers value through a chat interface, you have to provide dialogue as an affordance.

There are lots of different kinds of conversations that people have. Do you approach the LLM as an all-knowing oracle or a creative companion or a virtual assistant or something else? What needs to be apparent when someone enters a conversation with an LLM? Looking again at how a conversation is entered with an oracle or a creative companion or an assistant provides some hints. An expert may present themselves as having a degree, a wizened face, a tweed coat with elbow patches, or an office in a old, ivy-covered hall of knowledge, but it’s over the course of a conversation with them that you move towards a better understanding. A creative professional may have a bright office filled with primary colors and whiteboards, but it’s through collaborative discussion that you get inspired and flesh out your vision. The best assistance comes from your relationship with an assistant, too. Not transactions, but dialogue. (Maybe even dialogos!)

Ok, so how to make this concrete in terms of a chat interface, and how do you know if your design is working for people? I’m a communications professional, not a product person, so I can only gesture in a direction, but if there’s a way to quantify how well a query partitions a space of information, that could be a good place to start to figure out if your expert is engaging in effective dialogue and leading someone to a better understanding. To take a simple example, imagine someone asks for gift ideas. If you tell the salesperson at a fancy retail store that you’re looking for something for your mom, they’ll ask what occasion, because occasion is one of the main ways gift-giving is partitioned. A chat agent should afford carving up of the information space in a similar fashion. An LLM contains multitudes, so it doesn’t make sense to put ChatGPT in a tweed coat, but that’s not important. The important thing is that there’s process of dialogue through which understanding or inspiration or whatever is approached.

Outsourcing judgement, the AI edition

With every new technology, people try to do two things with it: communicate with others and rate people2. AI is no exception and HR and communications professionals should expect it to show up in two places: social media analysis and candidate screening.

Over the past 13 years, I’ve become an expert in many different ways to rate people, from the academic citation analysis tools on which universities spend millions to dating apps, and I’ve used a number of tools to monitor social media. The tools are dangerous to your business if you don’t know what you’re doing. You absolutely cannot assume social media is an accurate reflection of actual customer or consumer sentiment3. Social media monitoring tools will show you thousands of mentions from accounts with names like zendaya4eva and cooldude42 and the tools roll everything up into pretty dashboards that summarize the overall sentiment for you. There’s just one problem, and it’s that social media sentiment analysis sucks. Posts aren’t long enough for the algorithms to get enough signal and they can’t detect sarcasm or irony. You’re better off just looking at a sample of posts than using a sentiment dashboard. Analytics vendors know this and they’re working on building AI into the tools to make this better, but if you’re looking at social media sentiment because it’s easier to get than data on actual customers, you’re like the proverbial drunkard, looking for your keys where the light is better rather than where you actually lost them, and no amount of AI can fix that.

Candidate screening tools make some of the same promises. We can analyze the social media history of a candidate and flag areas of concern! I’ve written social media policies4 for several organizations and never have I ever seen a hiring or firing decision depend on a social media post that required a tool to flag. It’s very tempting to outsource our judgment. Thinking is hard and people aren’t always very good at it. You might think it’s better to have an objective process that eliminates conscious or unconscious bias5, but when you do this, you’re taking agency out of the hands of HR and the hiring manager. Hiring is a hard, multi-factorial decision and the last thing you want to do is outsource judgment here6 .

Progressive summarization of audio & video to retain more of what you hear in podcasts & watch in online lectures.

I read a lot, and in a lot of different places. Sometimes I’m just reading for fun, but when I’m reading something that I want to remember and be able to share with others or apply in my own life, I have found annotation and progressive summarization to be effective approaches. These approaches generally require text, but with the addition of a few services that mostly play nicely together, you can extend this approach to audio and video.

Prerequisites

Accounts at Otter, Readwise, Hypothesis, and Roam.

The Hypothesis toolbar in your browser of choice (I like Firefox).

The Process

Let’s say you’re watching a lecture. Instead of trying to scribble notes in a notebook that you’ll later have to transcribe into Roam, you open Otter and let it start creating a text transcript. Take pictures or screenshots as you go, because Otter will be able to place those in the transcript according to timestamp. When it comes time to review, you use Hypothesis to annotate the Otter transcript, then you write some notes in Roam summarizing the insights from the lecture. If you’ve connected your Hypothesis account to Readwise, your highlights will be occasionally re-surfaced for you to review, which is a key step in making them actionable. There’s also a way to get spaced repetition in Roam.

The Setup

At Readwise, you have a bunch of options for connecting highlights. Enable Hypothesis and it will pull in all your highlights from Hypothesis, including the ones you’ve made on the Otter transcripts. You’ll find them under the Your Articles section at Readwise. You can review there and write up summaries in Roam, linking to other concepts and notes.

Why It Works

It works for me because I use Readwise as a sort of catch-all bucket for all the stuff I already read in so many places – Kindle, Twitter, and all the stuff I find via Twitter and shove into Pocket – and now I can also use Otter to convert things I listen to or watch into a form that Readwise can catch & periodically re-surface for me.

Caveats

- When you select ‘view in article’ at Readwise, it will take you to Hypothesis, not Otter. Otter can generate sharing links to annotate or you can export the transcript and annotate it somewhere else that’s publicly accessible, which is probably the best course so you have your own backup.

- Making extensive use of all these services costs a little money. Readwise is a couple bucks a month, and Otter costs a little bit if you go over their free minutes. Roam likewise has a subscription plan. I personally believe that if you are going to invest a lot of time and effort into building a personal knowledge management system, you’re going to want that system to stick around and get better, so you’re going to hope they charge enough to do so, but I know even a couple bucks a month can be hard to come up with on a grad student budget, so here’s some options. Most YouTube videos have a transcript generated by Google, which may be of higher quality and won’t use up your Otter minutes. Also, Docdrop is a service from the founder of Hypothesis that facilitates annotation of all sorts of document types and can accept Youtube links.

- These services are all relatively new. There is a possibility that they go under or get bought by a company with a different privacy policy. Carefully inspect the privacy policies of all the services you use, consider not using services that don’t let you delete or get your content out easily (Evernote, for example), and keep your own backups. I will note that services getting acquired is not necessarily a bad thing. My company, Mendeley, was acquired by Elsevier 7-ish years ago and it’s still going strong. Also, services that charge money tend not to be as intrusive to your privacy.